A Murdochian Metaethics

I currently hold a Leverhulme/Isaac Newton Trust Early Career Fellowship to work on a project looking at Iris Murdoch’s moral philosophy: ‘Moral Vision and the Good: Murdoch as a Guide to Meta-Ethics’. In the project, I hope to uncover and reconstruct Murdoch’s metaethics, the second-order commitments on the nature of the ethical realm that underlie her thinking.

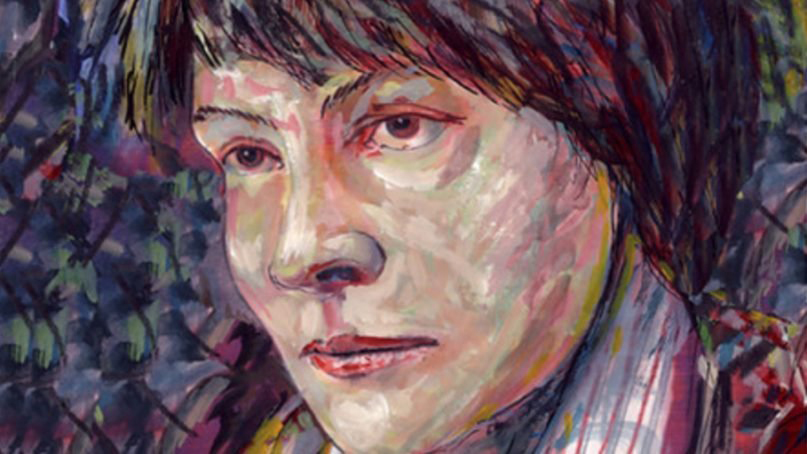

I first discovered Murdoch as an undergraduate. I spent a summer dabbling in various philosophy books I hadn’t come across in the course of my usual studies, and was intrigued but perplexed by her brilliant The Sovereignty of Good (intrigued and perplexed enough, that is, to return to her the next summer even though I had understood very little of it). Despite the fact that her work was written many decades ago, so many of the ideas resonated with my concerns about contemporary moral philosophy, and her vision felt inspiring and somehow appealing, though I would have been hard pressed to explain why.

Since then, Murdoch’s thought has made its way into lots of areas of my research, and I’ve been particularly interested in her conception of love and its connection to knowledge. Love is relatively rarely discussed in current philosophy, and when it is discussed, it is often thought of as something affective (a certain inward ‘feeling’) rather than cognitive (something involving beliefs or knowledge about the world). Murdoch’s insistence that love involves knowledge is, I think, crucial to her conception of it, and I find it a very appealing part of her view. In one paper I thus explore exactly what Murdoch takes the relation between love and knowledge to be, and why. I’ve also explored what the implications of this view might be for some current debates about friendship. It’s a popular view in the philosophical literature on friendship that friendship can involve having positively biased views about the other person (seeing them as more skilled, more interesting, more moral and so on than our evidence suggests that they really are). This is known as ‘epistemic partiality’. In another paper, I suggest that the view that friendship involves epistemic partiality must be mistaken, because it ignores the Murdochian thought that friendship (like all love) involves knowledge, and a progression towards better and deeper such knowledge.

My current project attempts to produce a more systematic understanding of Murdoch’s moral philosophy than I’ve previously attempted. Murdoch’s ethics, which are currently commanding considerable (well-deserved) attention, offer novel and incisive answers to many questions that are of perennial interest to philosophers, and there is an increasing sense that her moral philosophy captures some of the most important and under-theorised aspects of our ethical lives, like the common phenomena of love or selfish blindness. However, her ethical thought radically departs from the framework assumed by many ethicists today, and she is hard to fit in to any of the existing taxonomies for ethical thinkers (which may be partly to blame for the relative neglect of her work). Despite the recent renaissance of interest in her work, relatively little sustained attention has been paid to the overarching background of her philosophical work, the unorthodox Platonic metaphysics that underlie her philosophical vision.

This relative neglect raises (at least) two worries: first, by drawing on the particulars of her work whilst ignoring the general philosophical backdrop to those claims, we risk distorting Murdoch’s thinking. Second, in doing so we may be blind to the distinctive contributions that her work has to offer contemporary ethics, and we may end up ignoring her most valuable insights. In my project, I am developing a Murdochian metaethics, an account of the second-order commitments on the nature of the ethical realm that underlie her thinking. In developing this systematic framework, I hope to shed light on various long-standing problems for contemporary moral philosophy regarding the nature of moral knowledge, moral motivation and moral objectivity.

Central to Murdoch’s metaethics is the Platonic idea of ‘the Good’, which she sees as a secular analogue to the concept of ‘God’ that has a certain ‘magnetic’ draw. This idea can seem both appealing in giving us an authoritative moral standard and so on, and yet slippery: what exactly is it supposed to be? What would such a ‘demythologized religion’ really look like? And what would it mean to love the Good itself? Murdoch makes much of the parallel between God and Good in her work, suggesting, for example, that contemplation of the Good can assist us in moral development (which she suggests is a secular analogue to prayer). Murdoch also describes the Good as a transcendent reality, but all the same she distances herself from commitment to its existing in any robust metaphysical sense, suggesting that it doesn’t exist ‘as people used to think God existed’.

In this project, I am exploring how Murdoch envisages the Good and conceives of it as having an action-guiding role in our moral lives whilst avoiding committing to its metaphysical existence. As part of this, I am investigating the parallels between conceptions of God and the Good in Murdoch’s work, and examining what Murdoch refers to as the ‘Ontological Proof’ of the existence of the Good. This fascinating argument is framed by Murdoch as being based on Anselm’s argument for the existence of God, whilst nonetheless arguing for a different conclusion: that the Good exists. What’s more, her argument (unlike many traditional interpretations of Anselm’s argument) is not a priori, but based on our moral experience: her suggestion is that our ubiquitous experience of imperfect goodness points towards perfect goodness, i.e., the Good itself. Unconventional though this argument is, I think it is also appealing, and it offers a novel approach to thinking about the reality of goodness. If there is a productive interpretation of Murdoch’s work here, it would provide contemporary philosophers with an attractive model for understanding moral objectivity, and an interesting and persuasive new argument in favour of it.