Poetry for the Soul: Murdoch’s Philosophy and Poetry as Vital Resources for the Modern World

In the summer of 2023, I completed my master’s dissertation entitled ‘Where Words Begin: Breaking the Illusion of the Self in the Poetry of Iris Murdoch’. This blog post contains exerts from my thesis, as well as more broader references to the significance of the discovery of Murdoch’s lesser-known body of poetic work to our understanding of her philosophy of unselfing.

At this time of year, as the winter equinox enfolds the northern hemisphere in her arms and turns light to darkness, the world seems to quiet with introspection. This is the time that the battle with the self becomes most intense, most ravaging and potentially damaging to my soul. At times like this, I am reminded of Murdoch and her kestrel; the hovering force that was able to pull her away from the ‘brooding self with its hurt and vanity’. Looking out of my window into the grey stained air, it seems difficult to believe that my attention could be pulled away so directly by such a fickle thing as nature.

What I am of course referring to is Murdoch’s philosophy of ‘unselfing’, a term first coined in The Sovereignty of Good in the 1970s. While the term itself was original, Murdoch’s attempts to grapple with concepts related to the morality of the self followed a trajectory laid down by centuries of her predecessors. One cannot fail to see parallels with the likes of Keats, for example, whose theory of ‘Negative Capability’, an idea that argued for attention to beauty and the freedom of the imagination, was epitomised in his poem 'Ode to a Nightingale':

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves has never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan.

The weariness, fever and fret was of course something Murdoch was far too familiar with, having witnessed and lost loved ones in two brutal wars in the first half of the 20th century. Suspicion of the liberal mind by revered writers such as T.S. Eliot and criticism of language to explain the human condition truthfully by poets such as W.H. Auden propelled the question of the self into turbulent waters. While we can see reflections of Romantic notions of attention to nature in Murdoch’s philosophy and writing, she is suspicious of being taken too far away from the self. The speaker in Keats’ poem, for example, is tempted, siren-like by the nightingale he never sees and carried away to a place of ultimate disappointment: he returns to himself having pursued a fruitless form of escapism. Murdoch’s attention to nature is filtered through the disappointments and suspicions of the 20th century and asks not to be lured away by a song, but demands that we simply pay attention to what we can see in front of us. In her novels, her intensely real characters are placed on a scale of human selfishness, with Murdoch magnifying their flaws and desires as they grapple with themselves. In The Bell for example, readers watch Dora’s futile attempts to escape herself, her almost comedic attempts to be a better person falling short at the point of delivery. It is Catherine’s battle with the self that is tragically shown to be the most damaging, however. Like the speaker in 'Ode to a Nightingale', she projects her fears and struggles onto a holy other, only for them to hit her even harder when she realises she cannot escape herself.

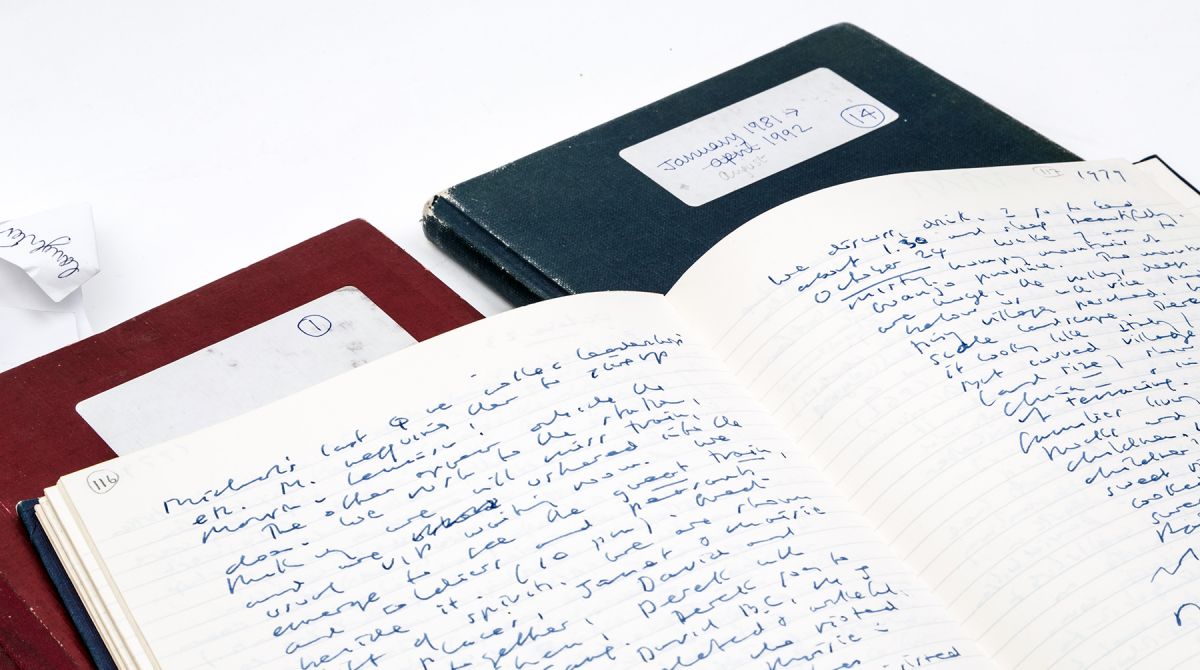

Despite the realism of her characters, it is the poetic form that Murdoch uses as her playground to explore and battle with the philosophy of unselfing. Over the summer I had the pleasure of visiting the Iris Murdoch archives at Kingston University and exploring a selection of poetry from the Wallace Robson collection written in the early 1950s. Never intended for publication, the poems lack the polished, self-conscious finish of her published texts and allow us to view her philosophy in its true, human environment. Read thus, Murdoch’s attention to the ordinariness of nature can be seen in numerous metaphors and images of birds, spiders and stars. Simply put, Murdoch’s poetry is an attempt to unself, something that can be clearly seen in ‘Poem 13’ of the collection. Dated 25 February 1952, it is one of the earlier poems in the collection and comes towards the end of her relationship with Wallace Robson. In this poem, Murdoch extends the metaphor of the bird to describe the simple goodness of her lover’s heart. She describes how these birds have been held captive by her heart and how she wishes for them to return to him, hopefully unscathed. The breakup causes deep emotions, but she returns attention to the innocence and goodness of the birds to move away from her own grief. The poem is made up of five stanzas of five lines in which the first, fourth and fifth lines rhyme, with a separate rhyming couplet in lines two and three. It follows a series of poems on the theme of truth, featuring natural imagery such as birds. In ‘Poem 13’, Murdoch discusses the purpose of poetry and the power of words over the self:

Instead of a letter it eases

The heart more to write this.

The great thing is to avoid fuss.

The deep impulse is to do what pleases,

Though perhaps the result only teases.

The acknowledgement in the opening two lines that poetry is more effective at expressing the heart’s desires than a letter reflects the transactional nature of Murdoch’s poetry. The fact that Murdoch often sent poems to lovers and friends conveys her need for deep and meaningful connections that she believed could only be achieved through unselfing; the lack of an ‘I’ in the opening is integral to the pursuit of the 'other-centred concept of truth' she discusses in her essay ‘Against Dryness’. The lack of an 'I' also opens the poem up to the idea of a collective experience; there are many instances in the opening where an 'I' would feel more natural compared to the deliberate attempt to discard it, but this allows for a more universal tone to permeate the lines. Furthermore, she acknowledges the 'deep impulse' to gravitate towards sincerity rather than truth, and there is a sense of heady sensualism in the opening to the poem with the very deliberate (and somewhat forced) rhyme of 'eases', 'pleases' and 'teases'. The focus on pleasure at the end of the lines perhaps points to the self-reverential liberalism opposed by writers like Eliot, further reinforced by the references to 'the great thing' and 'the deep impulse'. The synonymous references to size both emphasise the challenge and reward to humankind; the challenge being to avoid the temptation to use language in a way that removes meaning through senseless expressions of the self, and the reward being the 'great thing' that emerges as a result of self-sacrifice. The bathos in the final line reinforces the notion of the self as a tempting but ultimately disappointing focal point of attention.

Despite this realisation, her poetry also highlights moments of failure in her attempt at unselfing; entombed in dusty notebooks, Murdoch’s poetic battles with the self rage on from page to page. It is strangely comforting that the 32-year-old Murdoch, fighting through loss and heartache, desire and disappointment, attempted time and time again to move attention away from herself in order to be a better person. It is the fact that I find myself staring out of the window on a cold winter’s day, looking for something to focus my attention on, over 50 years after she first coined the term ‘unselfing’ that makes Murdoch’s philosophy and poetry incredibly relevant and important resources for the modern world; a world where the wellbeing industry has become endemic with adulterated, culturally appropriated versions of mindfulness and meditation popping up in urban spaces, promising enlightenment, a means of reconnecting with the digitalised world – escapism. That it has become a multi-billion-pound industry is perhaps testament to the fact that the human condition remains a highly ambiguous and contested area of philosophy; our big ideas have let us down and we are drawn towards the need for a more simplistic approach to our own human messiness. What else, after all, is mindfulness, a reappropriated buzzword in popular culture, if not attention away from the self? Murdoch’s poetry reminds us that discarding the self is an important but messy process, one that is not linear, but one we should all strive to do to achieve a morally good way of life. Murdoch’s poetry reminds us how to be human, it is, as Hilary Burde notes in A Word Child, 'where words begin'.