A Clockwork Iris

My favourite idea in Murdoch's notable 1961 essay ‘Against Dryness’ is that of the rare ‘written’ novel (the italics are, memorably, hers). It introduces a line of argument that is an instance of the ‘confident, ambitious breadth of reference’ Peter J. Conradi mentions in his preface to Existentialists and Mystics:

Most modern English novels indeed are not written. One feels they could slip into some other medium without much loss. It takes a foreigner like Nabokov or an Irishman like Beckett to animate prose language into an imaginative stuff in its own right.

However, the very next year saw the publication of a book written by an Englishman, Anthony Burgess, which is a prime example of the ‘linguistic quasi-thing’ that Murdoch believes a novel can be: A Clockwork Orange. Its ‘Humble Narrator Alex’, an ultra-violent’ adolescent delinquent, has not just a distinctive voice but a distinctive tongue, ‘nadsat’, a Russian-saturated teen dialect. The vivid animation is there from the very first page: ‘and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry’.

Almost a decade later, when Stanley Kubrick made his controversial film version of A Clockwork Orange, Burgess’s novel passed the Murdoch test: it did not slip into the cinema without notable loss. As David Lodge remarks in The Art of Fiction (1992):

… [the novel’s] stylized language keeps the appalling acts that are described in it at a certain aesthetic distance … Kubrick’s brilliant translation of its violent action into the more illusionistic and accessible visual medium made the movie an incitement to the very hooliganism it was examining, and caused the director to withdraw it.

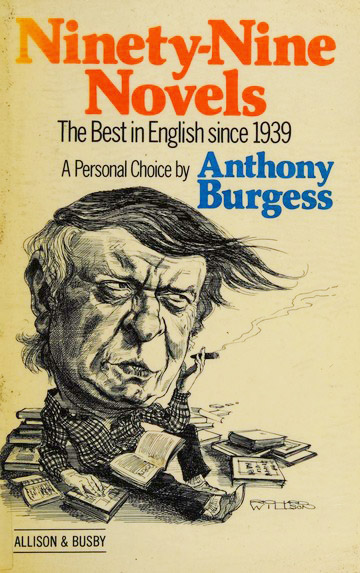

Even though the Korova Milkbar and the Duke of New York pub, those dystopian dens of iniquity, seem a world away from the contemplative atmosphere of Imber Court and Imber Abbey, I think there’s a surprising affinity between A Clockwork Orange and Murdoch’s The Bell (1958). For a start, Burgess included The Bell in his 1984 canonical exercise Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939 — A Personal Choice.

Since early 2022, the International Anthony Burgess Foundation has been releasing episodes of a podcast dedicated to a discussion of the novels on the list. I’m sure many Murdochians will already be familiar with the excellent episode on The Bell. It features host Graham Foster in conversation with Professor Avril Horner. She sees Burgess’s inclusion of The Bell implicit in some of his introductory remarks in Ninety-Nine Novels:

It is the Godlike task of the novelist to create human beings whom we accept as living creatures filled with complexities and armed with free will.

Horner then talks about Murdoch’s fictional and philosophical engagement with free will. And I might add that Burgess’s literary credo could live right next door to the famous assertion at the close of Murdoch’s 1959 essay ‘The Sublime and the Beautiful Revisited’: ‘A novel must be a house fit for free characters to live in …’.

These lofty aesthetic ideals at first seem incongruous when we turn back to consider the bloody circus that is the world of A Clockwork Orange. After all, little Alex and his gang of ‘droogs’ are more obviously armed with sharp weapons than with free will, and on entering any Murdochian fit house they would trash the furnishings and attack the residents.

Beneath the verbal performance and disturbing mayhem, however, runs a sober philosophical current. Burgess is in fact deeply concerned with free will. ‘The important thing’, he says in his 1986 introduction to the revised American edition of the novel, ‘is moral choice’. That edition essentially involved the inclusion, for the first time in the USA, of the novel’s 21st and final chapter. This, the novel’s true ending, is an account of Alex’s freely chosen – as opposed to his earlier state-imposed – reformation. According to Burgess, back in the early 1960s his American publisher had demanded that the last chapter be dropped, deeming it a ‘sellout’. For Burgess it was the point:

There is, in fact, not much point in writing a novel unless you can show the possibility of moral transformation, or an increase in wisdom, operating in your chief character or characters.

Now, this sounds eminently Murdochian, particularly that ‘increase in wisdom’, the wages of the philosophical good life. Indeed, in discussing The Bell, Avril Horner describes Dora Greenfield’s visit to the National Gallery as the occasion of ‘a moral improvement, a moral jump’. In the light of these comments, I reread that epiphanic scene. Dora’s ‘increase in wisdom’ comes from seeing anew familiar masterpieces, especially Gainsborough’s ‘The Painter’s Daughters chasing a Butterfly’.

It would be hard to imagine a picture of youthful activity more different than the vile antics of Alex and his peers. But the question that haunts A Clockwork Orange like an Eliotic refrain — ‘What’s it going to be then, eh?’ — also haunts the National Gallery scene: the question of moral choice. Of course, in those environs, it’s not expressed with such colloquial insistence. But the task facing Murdoch’s ‘chief character’ in ‘the eternal spring-time of the air-conditioned rooms’ is still the same: ‘It was as good a place as any other to decide what to do’ (here the italics are mine).

Actually, it turns out to be a very good place to decide what to do. Dora has the paintings on her side. At the heart of the scene, as Avril Horner points out, ‘is a secular revelation that comes through art’. The timely lesson the paintings teach Dora is that there is ‘something real outside herself’. They both console and prompt her. Soon she on her way back to the place which is currently the true locus of her life: Imber.

In providing that spiritual service, the great paintings remind me of a phrase from Saul Bellow, Burgess and Murdoch’s major American contemporary: ‘reality instructors’, though in Bellow’s novels those teachers tend to be street-smart characters more akin to Alex than Gainsborough.

But here’s a twist. It is not just Dora, but also Alex who is moved by fine art. After her reality instruction, Dora is aware that ‘her face must have looked unusually ecstatic’. And, as Martin Amis commented in the New York Times back in 2012, Alex’s ‘ecstatic love of classical music’ is the ‘wayward brilliance’ in Burgess’s characterisation of his anti-hero. Composers, however, don’t provide Alex with any moral instruction, not even his idol ‘Ludwig van’. Instead, he brags, ‘Music always sort of sharpened me up’.

Even when Alex’s musical taste begins to mellow, in that transformative final chapter, his soundtrack is much more of a reflection than a shaper of his moral mood. Great art, one could still argue, however, is nonetheless working upon him. Alex has become disillusioned with his gruesome lifestyle ‘of the old ultra-violence and crasting’, and in his despondency he unwittingly channels Hamlet. When he tells his cronies ‘I know not why or how it is’, he echoes the prince informing his droogs, ‘I have of late — but wherefore I know not — lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises’. (Richard E. Grant’s down-and-out recitation of this speech in the 1987 film ‘Withnail and I’ brings the ramparts of Elsinore and the gritty streets of A Clockwork Orange together beautifully.)

In their prolific writing careers, both Burgess and Murdoch had a sustained and inspired conversation with Shakespeare, but that shared aesthetic passion deserves an essay of its own.