‘Iris Murdoch Today’ Series

In 1971, Iris Murdoch wrote to Brigid Brophy:

I have become a convert to Powellism. (Anthony not Enoch). I believe I am in love with Widmerpool. Isn’t it terrible?

Seeing this among Murdoch’s letters in Living on Paper made me think again about her connections with Anthony Powell.

It must have been sometime in the late 1970s when a friend introduced me to Powell’s twelve-volume novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time. I soon became a convert and have read the books many times since: first in England, then in Japan where I was to move, and most recently on the island of Okinawa where I have lived since 2009.

Powell’s long tale concerns the lives of a vast array of characters and takes place over a large portion of the 20th century. The story unfolds as told by the narrator Nicholas Jenkins, a person whose life has much in common with his creator Anthony Powell. Jenkins goes to an unnamed public school (probably Eton) and then to an unnamed university (Oxford?) before working for a publisher in London. He becomes a novelist and critic, and in later life settles in the countryside as did the author in Somerset.

The Dance volumes begin with A Question of Upbringing (1951) and conclude with the publication of the final book Hearing Secret Harmonies in 1975. In the year of Murdoch’s letter, the tenth volume, Books Do Furnish a Room, was published and so the series was still ongoing.

The character that Murdoch believed herself to be in love with is the plodding but power-obsessed Kenneth Widmerpool, an awkward figure of fun as a schoolboy who subsequently appears at regular intervals throughout Jenkins’ life to become a major recurring character in Dance. Many readers see Widmerpool as monstrous, but he is also a great source of comedy, and with a pitiable side that clearly appealed to Murdoch.

I discovered Iris Murdoch’s novels around the same time that I was becoming immersed in Powell. I had read a few in England, starting with The Bell, before my move to Japan in the mid-1980s. By chance, I soon discovered a Japanese professor at the university in Kobe where I was teaching who had a complete set of Murdoch novels in hardback on the shelves of his office. I visited him regularly to borrow each of them in turn until I was up to date. And so, I became a Murdochian as well as a Powellian.

The writing styles of Murdoch and Powell are quite different, but on the surface their novels deal with common settings – particularly London – and focus on the lives of mainly white upper-middle-class characters. An oft-repeated criticism of both has been the narrowness of these exclusively privileged worlds but this rather misses the point as the concerns of these people are universal and the novels can surely be appreciated and identified with by any sympathetic reader.

Murdoch employs first-person male narrators in some of her best novels such as A Word Child, The Black Prince, and The Sea, The Sea and her narrators tell stories of great intrigue and suspense frequently focused on their own misguided view of events and growing realisations. By contrast, Nicholas Jenkins is the ultimate reticent narrator who is far more interested in the lives of his contemporaries, friends, and acquaintances than he is in revealing anything much about himself to the reader.

There may, however, be an underlying connection in the genesis of both writers as novelists. At least there is according to A.N. Wilson, who writes in his book Iris Murdoch as I Knew Her:

“Anthony Powell’s Dance she read, saying that it was the product of an only child. Not only is the great sequence an account of an only child acquiring, through marriage, innumerable relations; more than that, an only child naturally peoples the world with imagined friends and siblings. Iris Murdoch used to say that she and Powell were agreed on this, that their lives as novelists had begun in their solitary childhoods.”

The two novelists were, in fact, well acquainted. Powell writes in his memoirs of phoning Murdoch in 1977. He had been invited to an international conference in Sofia, Bulgaria, and thought that she might also be attending. She wasn’t. But it was Murdoch’s husband John Bayley who provided the main connection. He writes in glowing terms of the Dance sequence and in his late trilogy of Iris-related memoirs he looks forward to reading old favourites such as Dance in the evenings.

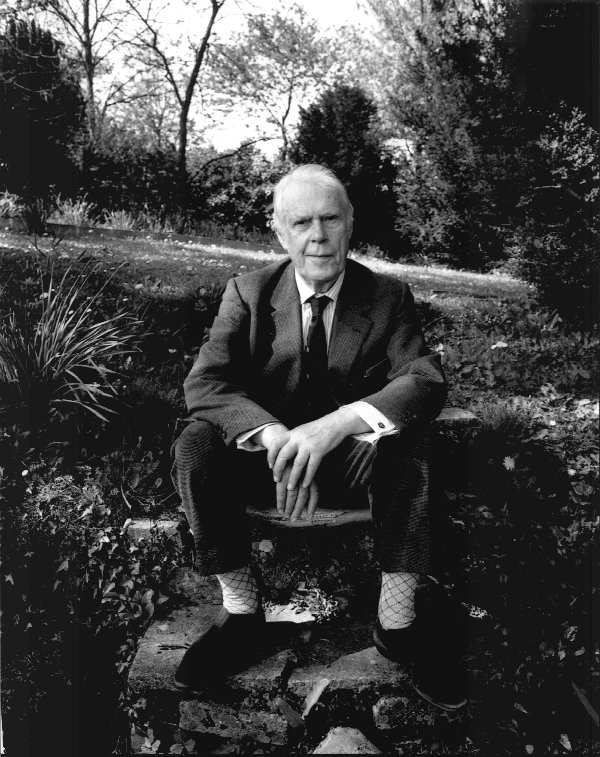

He was also asked to write the introduction to The Album of Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time which appeared in 1987. This was a large format book of mainly photos and illustrations related to the novel sequence and was edited by Violet Powell, the author’s wife. Bayley contributes the introductory essay 'The Ikon and the Music'.

The Powells and Bayleys were on such good terms that they visited each other too, and Peter Conradi’s biography mentions Bayley cooking dinner for them when the Powells were guests at Cedar Lodge. The four also met up in May 1983 when they spent a weekend at Whitfield in Herefordshire at the house of Powell’s sister-in-law. Of this weekend Powell notes in his Journals:

“Iris somewhat put out by reviews of her recently published novel The Philosopher’s Pupil. These might have been thought not too bad, though one knows only too well that reviews look quite different to the author from the impression given to other writers, and the general public.”

He also writes, of the same weekend, that Bayley was in good form and is “one of the best, most sensible contemporary literary critics…” Bayley was similarly quick to praise Powell as a critic.

Visiting The Chantry, the Powell family house near Frome in the Somerset countryside, could, however, be quite an intimidating experience and Bayley says it was: “a bit like a permanent viva. You felt you had to have amusing, intelligent or original things to say.” In an interview with Michael Barber, one of Powell’s biographers, he says that when invited there with Iris, “Tony got what he could out of her, which wasn’t much, and then rather lost interest.” (In Powell mitigation, I met very briefly with John Bayley when he and Iris visited Kobe in 1993 and he told me simply that Powell nevertheless seemed ‘a nice chap’).

If visiting The Chantry could be a bit daunting, the Powells were somewhat nonplussed on a visit to Steeple Aston reported on by both Peter Conradi and A.N. Wilson. Conradi writes:

“Lady Violet Powell, wife of the novelist Anthony, was struck by the number of ageing Volkswagen Beetle cars secreted about the garden, which John reassured her were, ‘of course, a hedge against inflation’.”

In his Journals, Powell also enjoys repeating a story of their eccentricity told to him by someone who had been to dinner with them:

“Iris, while expressing some deep philosophic truth, removes the casserole from oven, and upsets it all over a beaded cushion. Without pausing in conversation, she reverses the cushion over a serving dish, gives cushion wipe, and dinner proceeds.”

It’s easy to see that Murdoch was an admirer of Powell’s Dance. Unfortunately, I can find no evidence of any reciprocal feelings for her own novels from Powell. He doesn’t review any of them and neither does he comment on having read them. They seem to have been off his literary radar. She was also of a slightly different generation, being almost fourteen years his junior.

The academic Elizabeth Dipple makes a rare allusion to Powell in her 1982 study Iris Murdoch: Work for the Spirit. In writing of Murdoch’s successfully prolific literary character Arnold Baffin from The Black Prince, she says:

“Tongue in cheek, she presents Arnold possibly as a parody of Anthony Powell, but also as what some critics have accused her of being because of her mysterious allusive frame and awesome prolificacy.”

I would be surprised if Murdoch really intended a parody of Powell as it seems more likely that she was simply parodying herself. What is true – and for this I am ever grateful – is that the two writers produced a very considerable amount of literary work. Aside from the Dance, Powell produced seven other novels, two plays, a book on the 17th-century antiquarian John Aubrey, and a great body of literary criticism now collected in three volumes. There are also collected Memoirs and three books of Journals. For her part, of course, Murdoch, has 26 novels to her credit in addition to her essays and works of philosophy.

The Anthony Powell Society, of which I became a founder member, was begun in 2000. There have been several conferences and publications since then, and there is a comprehensive website at www.anthonypowell.org.

John Potter