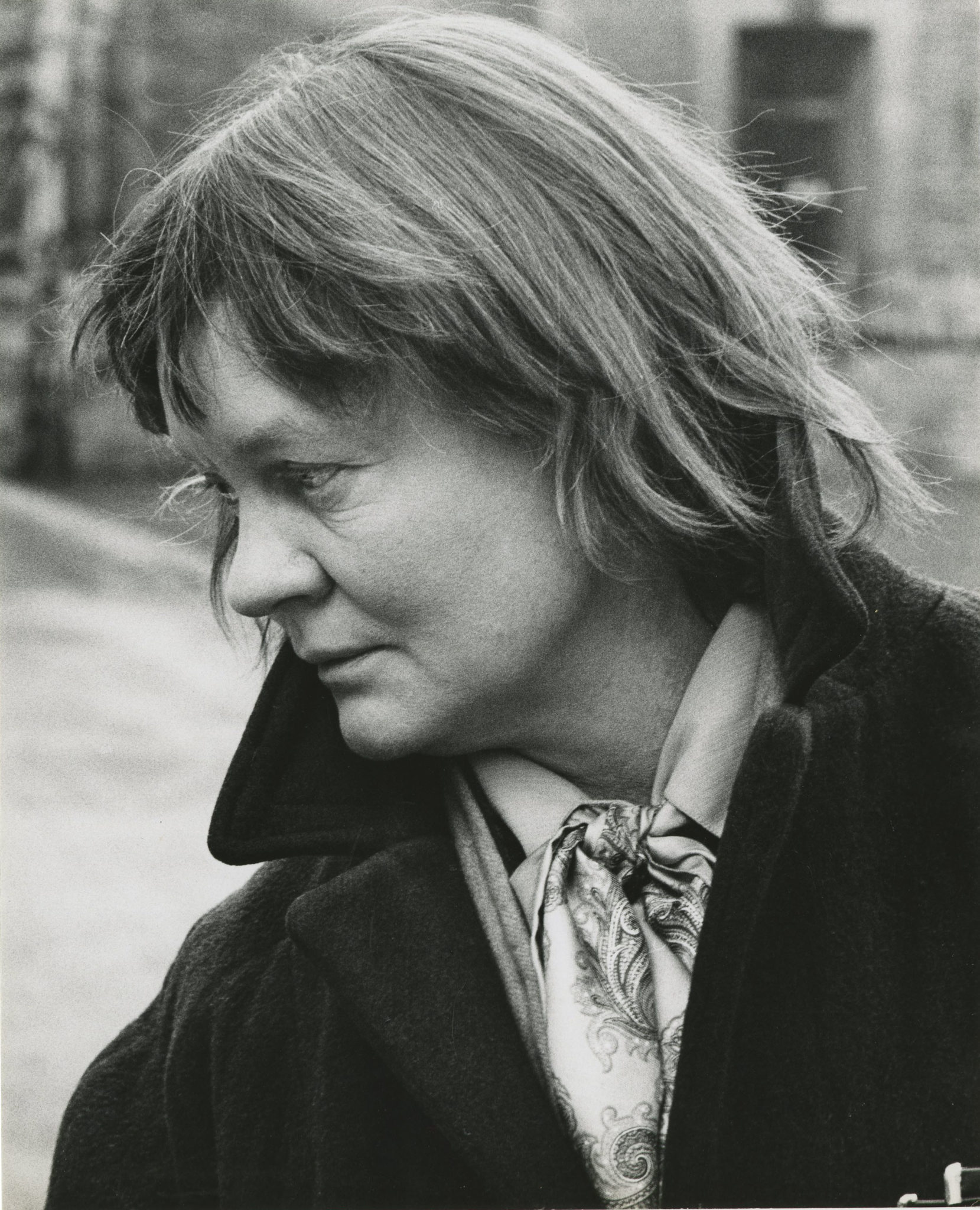

In this article, Miles Leeson follows on from his piece on Murdoch’s centenary last year and discusses the impact the Anglo-Irish writer is having on those who came after her.

Iris Murdoch, author of 26 novels, as well as plays, poetry, copious letters and philosophy, was never one to shy away from naming her literary forebears; she regularly praised the great nineteenth-century realist writers, ‘James, Austen, Dickens, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky’, for perfecting the novel form, as well as claiming that ‘Shakespeare was the patron saint of novelists as he invented free and eccentric personalities’. Murdoch’s early infatuation with Samuel Beckett and Raymond Queneau has been remarked upon, as has her personal friendship with Elizabeth Bowen: she felt much closer to them, she said, than major modernist figures like Joyce and Woolf. She also regularly claimed in interview not to read most of her contemporaries, although her letters and journals prove otherwise.

But what of those who followed in her wake? Certainly, the British and Irish postmodernists of the next generation had less time for Murdoch’s adventurous realism, but her influence can be felt in the range of writers who have claimed her as a touchstone. These include Ian McEwan, who read her voraciously as a teenager and can be seen as heir apparent to her form of moral seriousness; Zadie Smith, who claims that ‘occasionally I have wet dreams about turning into Iris Murdoch’; Sarah Perry, who claims that Murdoch ‘taught her to love the gothic’ from reading The Bell and The Unicorn; and Sarah Waters, who recently remarked ‘I’ve always been a big Iris Murdoch fan [I’ve] returned to her novels and remember how bloody good they are – how intelligent, how lucent, how divinely crazy’. Murdoch would be delighted to know that Irish writers like John Banville, Anne Enright and Eimear McBride are dealing with the same issues that she was in her fiction, the psychology of individuals and the messiness—or ‘thingyness’, as she would have it—of our day-to-day reality. Murdoch’s The Sea, The Sea (1978) and Banville’s The Sea (2005) not only won the Booker Prize but share a range of textual affinities—from a central older male protagonist to the reflections on love in early life.

Murdoch’s influence extends not just to novelists, but to all forms of creative writing. The Irish playwright, novelist and poet Jaki McCarrick has this to say about Murdoch’s influence on her own work:

In Iris Murdoch’s novel The Italian Girl (1964), the narrator Edmund Narroway states, ‘The question is not what life is best but what life can you best lead.’ This is a call from one character to another to pursue a more purposeful life. Such deeply thoughtful lines can be found throughout Murdoch’s oeuvre (as Gary Browning’s recent Why Iris Murdoch Matters illustrates, there is a philosophical underpinning to much of Murdoch’s fiction) and they make for addictive reading. As a writer, I find Murdoch’s fictional worlds, in which the “plot” revolves more around her characters’ moral dilemmas and the wisdoms they, like Edmund, arrive at, rather than lots of “action”, enormously liberating. I too am primarily interested in the inner lives of characters. I also adore the traces of mystery and magic in Murdoch’s work, such as the lost bell in the lake in The Bell, and the strange, almost menacing tone of The Sea, The Sea (in which the protagonist, Charles Arrowby, is a Prospero-like figure). These are qualities that stay with the reader long after the book has been read; they cling to the imagination. What writer wouldn’t love the ability to so bewitch their readers?

What all these writers, McCarrick included, have in common in their praise of Murdoch’s work is its steadfast refusal to become lightweight romance or sensationalist genre fiction. Although many of her novels do contain great declarations on love and sex—indeed, her work on the varieties of love is a central concern in both her fiction and philosophy—the novels never shy away from the difficulties of sustaining workable relationships. Murdoch’s first five novels, from Under the Net in 1954 through to A Severed Head in 1961, ranged across a variety of genres—from the European picaresque, across Gothic romance, to fictional restoration comedy—as she discovered the mode of writing that suited her best. As she moved into the more mature phase of her writing, these ideas coalesced around her central themes of love, attention to the individual, the weakness of the will and the damage men inflict upon women. Her novels are often referred to as shapeshifters—and they are—and yet the overriding themes of betrayal, damage and survival cut through all her works.

Garth Greenwell, in his introduction to the new edition of A Fairly Honourable Defeat, published to coincide with Murdoch’s centenary, says that:

the richness of Murdoch’s novel comes from its success, unequalled elsewhere in her work, in combining Shakespearean tragedy with Shakespearean comedy. As in ‘Much Ado about Nothing’, love is induced by flattery; as in ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, a conjurer shuffles affections like so many cards in a deck. To Murdoch’s rereading of Shakespeare is owed the peculiar nimbleness of this novel, its ease with ensemble scenes, its brilliant use of cross-cut dialogue. These are a few of my reasons for thinking that A Fairly Honourable Defeat, while not the most perfect of Iris Murdoch’s novels (that distinction belongs to The Bell), is decidedly her best.

Naturally, all the writers employed to write new introductions to the six novels that were reissued by Penguin Vintage last summer (among them Daisy Johnson, Sarah Perry and Sophie Hannah) have reasons to consider their particular choice the best; yet all of them agree that the work itself belies the earlier critical responses to her novels from the late 1980s onwards and following her death in 1999, when she fell a little out of favour. Two years after her death, Martin Amis, reflecting on the woman he knew during his childhood (through his father Kingsley), wrote that ‘Returning to her novels now, with hindsight, we get a disquieting sense of their wild generosity, their extreme innocence … her world is ignited by belief. She believes in everything: true love, veridical visions, magic, monsters, pagan spirits. Her novels constitute an extraordinarily vigorous imperium.’

Following the centenary celebrations last year, and looking forward to the future recognition of Murdoch’s work and legacy, it seems clear that both her ideas and her novels will continue to be read, discussed and reflected upon. Indeed, in the last few years Murdoch has been fictionalised in Paul Magrs’ Aisles, where she appears in an internet chatroom, and Steven Carroll’s A World of Other People, where she is placed side by side with T.S. Eliot. Given the diversity of continuing engagement with her fiction and biography, her place in the canon of British and Anglo-Irish literature is assured.

Miles Leeson is director of the Iris Murdoch Research Centre at the University of Chichester, England.