In this essay Miles Leeson suggests that the under-discussed friendship between Elizabeth Bowen and Iris Murdoch is one that warrants further attention

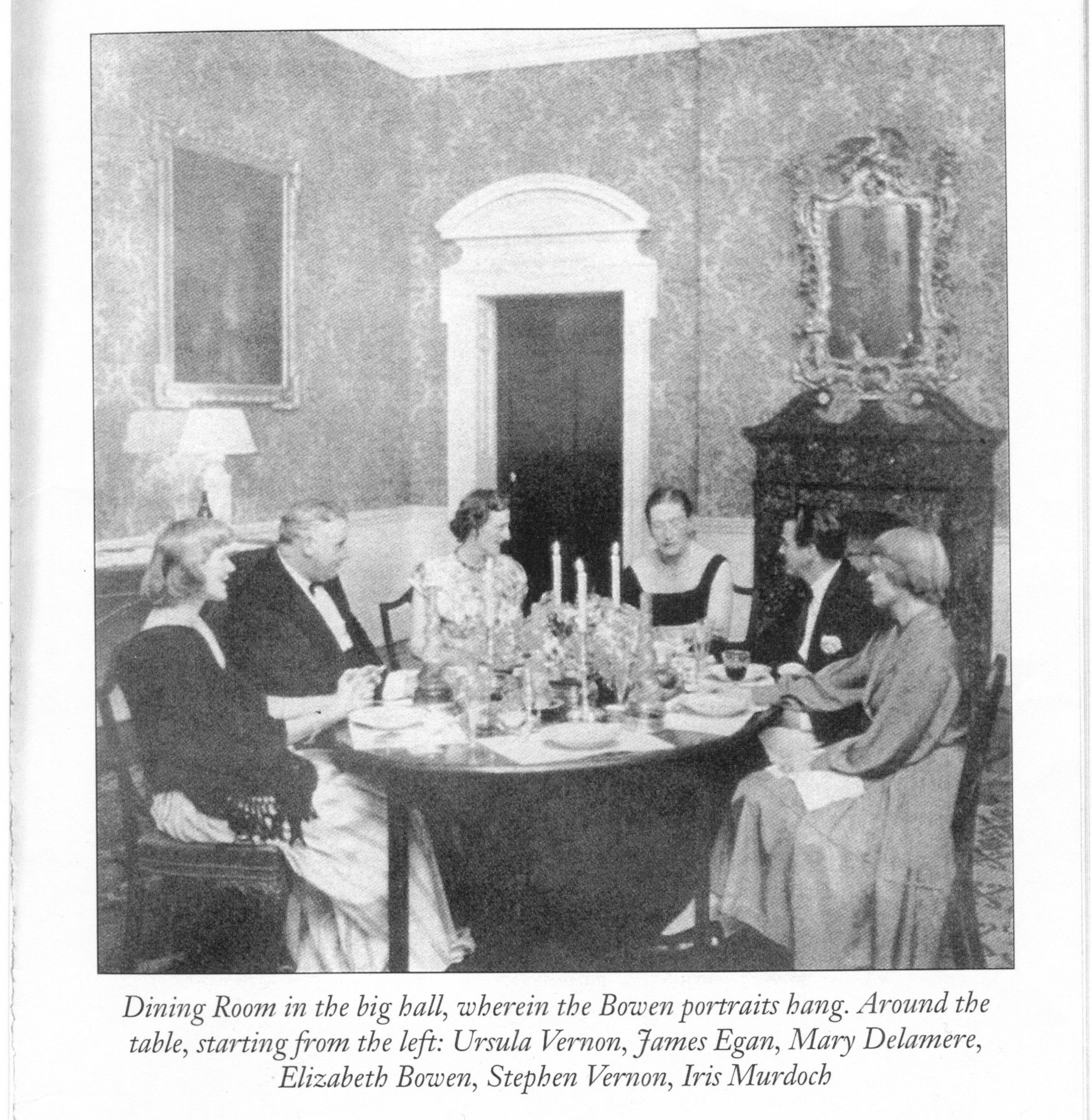

In my last essay I suggested that Murdoch’s ‘adventurous realism’ has had a strong influence on many who have come after her. Here, I want to suggest that Bowen was as least as important to Murdoch as the nineteenth-century writers she regularly praised. They struck up a friendship quite early on in Murdoch’s writing life, soon after the war, and she visited Bowen’s Court more than once. Murdoch’s visit in 1956 convinced her that her pending marriage to John Bayley could be much like that of Bowen’s to Alan Cameron: both intellectual and open. In a letter in 1988, she remembered their friendship and highlighted her appreciation of her fiction.

E.B. I like very much – especially Eva Trout and The Little Girls, and the short stories. I knew her quite well, as a friend, and I stayed two or three times at Bowen’s court … I was very fond of her. She should have been Queen.

Bowen and Virginia Woolf also developed a friendship—rather earlier, of course—and, although not a close one, each appreciated the other’s work. Bowen described Woolf’s genius as ‘some extra dimension that can’t ever be quite accounted for in terms of intelligence or emotion’ and when she was alone with Woolf she felt ‘awe and alarm. As a rule that wore off. But sometimes she seemed tired or extra remote.’ For Bowen, however, it was Jane Austen who was the overriding influence on her fictional writing and Murdoch, too, recognised the debt she owed to Austen.

Victoria Glendinning, in her biography of Bowen, states ‘She is what happened after Bloomsbury; she is the link which connects Virginia Woolf with Iris Murdoch and Muriel Spark’—and this is indeed the case. Murdoch’s early fiction—certainly from The Sandcastle onwards—is stylistically similar to that of Bowen and the narrative form that Bowen uses is imitated to an extent in Murdoch’s work. The two of them were friends until quite late on in Bowen’s life. Although Bowen was associated with the landed class of Ireland she too had roots on both sides of the Irish sea: both of them were caught between two worlds. Bowen’s novel The Last September illustrates this well, as it focuses on the social relations between the Anglo-Irish gentry and the occupying British forces—in effect, a prototype for Murdoch’s The Red and The Green, published 35 years later.

Glendinning believes, however, that with the selling of Bowen’s Court, Elizabeth severed the connection of the Anglo-Irish literary tradition with the motherland and so disassociates Murdoch from this tradition by default—a position that Murdoch would be surprised by, to say the least. At a conference in 1978 Murdoch rejected her association with the ‘English’:

Of course I’m not English, I’m Irish. But I live in England and I identify with the English novel tradition although I suppose some people in that tradition are Irish … as I say I’m Irish and I come from both sides of the border.

As Bowen was heard to remark over dinner, ‘Irish when it suits them, English when it does not’ in reference to anyone who termed themselves Anglo-Irish rather than ‘true Irish’. Indeed, the recurrence of Irish characters in Murdoch’s novels and the extensive treatment of the Easter Rising in The Red and the Green make explicit a persistent consciousness of Ireland as a considerable force within her fictional world. The resurfacing of these motifs and ideas within The Unicorn, The Sea, The Sea and The Green Knight seems to suggest an ongoing dialogue with both herself and her idea of nationhood.

It is natural in discussing the influence of Bowen on Murdoch’s fiction that The Unicorn and The Red and the Green should come to mind immediately, both being set in Ireland. The Red and the Green is her only historical novel and, perhaps because of this, the freedom of the characters within the novel is restricted by their lack of development through the narrative. I think it could just as easily, if it had been written by Bowen, been praised for its historical accuracy. Murdoch herself said that ‘I really did put a lot of work into that book … to my amazement I was able to get hold of all sorts of pamphlets that were written at the time and references to newspapers’—and the scene in which Andrew and Cathal race down to the Post Office toward the firefight at the end of the novel shows this to be the case. It is clear that Murdoch’s Dublin provides the inspiration, but Bowen provides the fictional link, and arguably the prototype. In The Last September a nostalgia for years past is, much as with The Red and the Green, placed beside the developing troubles with the British. Just as Andrew Chase-White is marginalised by his extended family for being both Anglo-Irish and a British soldier, so the British soldiers in The Last September are kept at a distance until they destroy the family home of Danielstown. This is, I think, reflected clearly in the way Murdoch describes Andrew in The Red and the Green. Another parallel is the juxtaposition of Andrew and Pat Dumay (the polar opposite of the Anglo-Irish cavalry officer and the Catholic freedom fighter). Bowen contrasts the major female characters of The Last September: Lois and Marda. Lois is younger, and eager to please her older and more elegant, detached (and consequently more Irish) relation. One is forever expecting a friendship that never materialises and the other barely registers the other’s existence—it seems that the idea of attending to others that Murdoch wishes her readership to engage with finds an echo in Bowen.

There are also echoes between The Unicorn and Bowen’s late novel A World of Love. Bowen’s novel is set in County Cork, an ‘expectant, empty and intense’ landscape whose only features is a dilapidated house fronted ‘somewhat surprisingly’ by an obelisk—a beautiful young girl then emerges from the house to read a letter. Murdoch’s novel is set in much the same environment in County Clare—the Burren—but it is what occurs within the house that is of greater interest. The owner of the house, Antonia, is confined to the bedroom and is guardian to Lilia. She marries Lilia off to a ‘wild, illegitimate cousin’ who himself installs a caretaker and relegates Antonia to the tower. This Gothic tale of romance and deception has strong echoes within The Unicorn (published some ten years later) and it seems unimaginable that Murdoch would not have read A World of Love and taken much from it. There are clear differences within the two novels, not least the symbolism Murdoch uses and the conflict between the inhabitants of Riders and Gaze Castle—the grounded and the mythical—which sets the tone of the narrative. Murdoch stated in an interview of 1985 that:

Hannah [her central character] is entirely different because the whole story has an allegorical aspect, and it’s much more mythical and less logical. Hannah is a figure who is either spiritual or demonic. The spiritual and the demonic are very close together. She’s either seen as a kind of noble victim or as a sort of belle dame sans merci, a femme fatale. She doesn’t know herself really, and it’s not clear what she is. She’s a power figure as well, with a great deal of effect on all these people and they in turn build her up.

There is also the role of women in her fiction, which, at least in these two novels, Murdoch takes from Bowen. She places Hannah at the centre of the narrative with The Unicorn but the movement of the narrative does not depend on her as she is stifled by the two major male characters; the mystic element in this work is of a similar nature to The Last September.

In reconsidering Bowen and Murdoch’s friendship we should not think the literary influence was a one-way street. Peter Conradi, Murdoch’s biographer, notes that there is a strong correlation between Murdoch’s experimentation with realism, and Bowen’s movement towards this in her final novel, Eva Trout; but this is a topic for another time. What is clear is that the lineage of the women’s writing extends beyond their own writing, back to Woolf and George Eliot, and forward to A.S. Byatt and contemporary female novelists.

***

Miles Leeson is the Director of the Iris Murdoch Research Centre at the University of Chichester, UK. @miles_leeson