‘It depends on the liver’: Alcoholism, Detoxification, Regeneration and Wound-healing in A Fairly Honourable Defeat

‘No more to drink, I have to look after my inside. Is life worth living? It depends on the liver. Freud’s favourite joke’; thus quips Julius King, quoting William James, via the pen of Iris Murdoch in A Fairly Honourable Defeat (1970) (1). Alcohol, in all its forms, features heavily in Murdoch’s novels and, in particular, four characters – Hilda, Morgan, Rupert and Simon – display serious alcohol dependency. Whisky alone is mentioned 52 times in the novel. Each character undergoes at least one significant life-changing event, which can either be blamed on or is initiated by excessive alcohol consumption.

In our bodies, the liver is the major site for alcohol metabolism and the acute phase of wound-healing after trauma. The liver has such reliable back-up mechanisms, spare reserves and capacity for regeneration that noticeable symptoms only manifest themselves when it is often too late to prevent complete liver failure. Similarly, while cracks steadily seep into the middle-class stability of the scene in A Fairly Honourable Defeat, the true extent of the damage takes a long time to make itself known. In this essay I will consider the cascade of drink-fuelled decision-making that drives the plot of A Fairly Honourable Defeat in the context of the molecular pathways for detoxification and wound healing implemented by the human liver.

How a professor of molecular biophysics became ensconced in the world of Iris Murdoch scholarship is a story for another day but, although I feel fully embraced by this academic community, I’m certainly an outlier in my education and approach, usually seeking parallels between scientific concepts and the novels’ plots. The theme of the Eighth International Conference on Iris Murdoch (September 2017) was ‘Gender and Trauma’ and from sleuthing through my email archive I deduce that, contrary to my usual habit of taking the theme as a starting point to alight on the topic of my paper, that year I was trying to find a way of weaving A Fairly Honourable Defeat into the theme because Julius King is a biochemist. I plumped for the trauma aspect by tying it in with liver disease. At the conference, more than one veteran participant (who shall remain nameless) mentioned that they planned to avoid my talk as they preferred to remain in denial about any effects alcohol might be having on their liver. Fair enough.

From my very first appearance at an Iris Murdoch conference in 2004, thanks to the encouragement of Anne Rowe to develop my ideas around the parallels between the forces explored in A.S. Byatt’s Degrees of Freedom (1965) and the energetics of protein folding that drive Alzheimer’s disease, I’ve always ad-libbed from a series of animated PowerPoint slides. Initially, this was because I was unaware of the traditional format for English Literature conferences in which people prepare their eloquently worded speech in advance and read it off a paper. Then the way I did it, science-style, went down so well that I’ve continued in the same vein ever since. The major disadvantage comes if I’m asked to submit my paper for publication because I then have to actually write it up coherently. I achieved this successfully with my 2004 paper ‘Alzheimer’s amyloid analogy: disease depicted through A Word Child’, which became a peer-reviewed chapter in Iris Murdoch: A Reassessment in 2006; my 2006 paper ‘Rebarbative Wire? Compartments and Complexity in The Bell and the body’ became a peer-reviewed chapter eight years later in Iris Murdoch Connected: Critical Essays on Her Fiction and Philosophy in 2014 (2). A charitable explanation for the discrepancy in the time delays might reflect the progression of my scientific academic career that leaves less and less time for my beloved Iris Murdoch. Whatever the reason, I was pleased for the push from Lucy Oulton and Frances White to write this one up and especially for the opportunity to adopt a flexible format and allow my quirky voice to come through. My other past papers on crowding (2008), indirect observance (2010), group dynamics (2012), pace (2014), sex hormones (2019) and energy landscapes (2022) will have to wait their turn.

What makes a novel alcoholic? In light of the above admission about my 2017 thought process, I deduced that I had not made a thorough enough case for choosing A Fairly Honourable Defeat as the tie-in for liver disease and decided to conduct some qualitative research to find out which is Iris Murdoch’s most alcoholic novel. I conducted a poll via the Iris Murdoch Society Facebook on 19 April 2024, and reached out to X (formerly Twitter) social media communities ten days later, asking which novel people consider the most alcoholic. I started with some suggestions and allowed others to add theirs to the poll options. Inevitably there arose some discussion on what makes a novel ‘alcoholic’ – is it the number of times drink is mentioned (either as an absolute figure or in relation to the book length), the total volume of alcohol consumed, the proportion of the plot that is driven by alcohol, or how much the plot deals with alcoholism? Obviously there can be no definitive answer to this question but to address the first, and only quantifiable, possibility, I took the four poll winners, A Fairly Honourable Defeat (in the lead on Facebook at 37% of 68 votes), A Severed Head (1961), Under the Net (1954) and A Word Child (1975) (in the lead on Twitter at 41% of 17 votes) and searched through each novel on my Kindle for mentions of a variety of alcohol-associated words (Table 1). I couldn’t run to specific wine types so, for example, the ‘two bottles of Puligny Montrachet and a bottle of Barsac’ that were ‘uncorked and put in the fridge’ for Simon’s dinner party, were left uncounted (FHD 64). Cider and rum occur in none of these four, so I’ve removed them from the table, despite cider featuring substantially in The Bell: a likely symptom of its West Country setting.

The numbers are impressive: A Fairly Honourable Defeat wins on overall mentions, but A Severed Head leads if one considers these results in proportion to the length of the novel (this concurs with Miles Leeson’s prediction on the matter). Hence I feel justified in focusing on A Fairly Honourable Defeat in this paper, particularly since my 2014 talk ‘Moving somewhere fast!’ (a quotation from one of Murdoch’s letters to the artist Harry Weinberger) examines A Severed Head in connection with the idea of ‘pace’ in technological progress (3). It’s also interesting to observe which novels feature which forms of alcohol, offering clues to their respective social settings, which are sometimes at odds with my memories of them. For example, Under the Net which in my recollections includes so many pints, apparently has only two mentions of beer, two of pint and none of lager. Morgan is largely responsible for the 52 mentions of whisky and while it seems to me, too, that ‘creamy champagne’ is guzzled constantly in A Fairly Honourable Defeat (AFD 32), thirty mentions of whisky possibly do more to fuel the plot of A Severed Head. Rachel Hirschler, one of the heroic Iris Murdoch Archive transcribers, muses,

I’m not sure which novel is the most alcoholic overall, but this quotation came to mind from The Sea, The Sea [1978]: ‘I walked back over the causeway, aware now of a dreadful headache and a swinging sensation in the head: not surprising, since, as I established later, James and I had drunk between us nearly five litre bottles of wine’ [4]. Wouldn’t like to work out how many units that is! [5]

The question struck a chord with many Murdoch enthusiasts: Michiel Borgman suggests The Unicorn (1963) as a candidate because of

the constant drinking of whisky. It is said that at Gaze, people drink whisky like water, and Hannah’s room has a familiar smell, whisky! Then there is the Burgundy Jamesie and Scottow have been drinking when they go shopping in Blackpool. And of course, the delivery of a new dress for Hannah is reason enough for drinking champagne, and ‘a better wine than usual’. I say: Cheers, Gaze and Riders folks! [6]

Charli Connor writes, ‘Great question! The Message to the Planet [1989] for me […] most of the characters could be described as intoxicated, through alcohol or delusions’ (7). And I enjoyed this musing from 19 April 2024: ‘I have often wondered what my life would be like if I followed the drinking patterns of her characters. Would I be more fun? Would I be dead by now? I’ve never fancied a mug of straight gin, but her characters seem to have no problem with it. Different times I guess.’ (8)

Tatevik Ayvazan, normally the first to champion The Italian Girl (1964), writes: ‘I was feeling positively drunk when I finished A Severed Head, without consuming any alcohol’. Others did suggest it, including David Morgan: ‘The Italian Girl? Otto is never sober, and if only for the precious description of him, as a man who would urinate in the sink even if a urinal was nearby (or something like that)’ and Daniel Read, ‘I’ve got The Italian Girl in my head, but mainly because it discusses alcohol addiction’ (9).

(Table 1: Alcohol statistics in the four Iris Murdoch novels voted ‘most alcoholic’.)

In 2017, my brother who lives in Gateshead put me in touch with a retired philosophy academic in Sunderland, Dr Arnold Spector, who had known Iris Murdoch. For a long time, and in true over-committed character, I have been working on a paper describing this friendship but here I just want to mention some interesting things he said about Murdoch and alcohol. Spector and Murdoch first made contact over the launch of a new journal Ethics in Literature for which she had agreed to join the editorial board. I share an excerpt from the transcript of one of my interviews with him in which he describes his own inadvertent pub crawl with Iris:

AS: …when we first met, so this was half-past ten in the morning, and she wanted to go to a pub. I think the first one was being decorated, so we moved on. The next one had a very noisy jukebox, so this was the third one, in Earls Court, when we first met, and she was drinking, at half-past ten, she was drinking orange juice with wine.

RI: Mixed together?

AS: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

RI: White wine?

AS: I don’t remember. I don’t remember. That’s what she ordered. I couldn’t face alcohol at that time in the morning. [10]

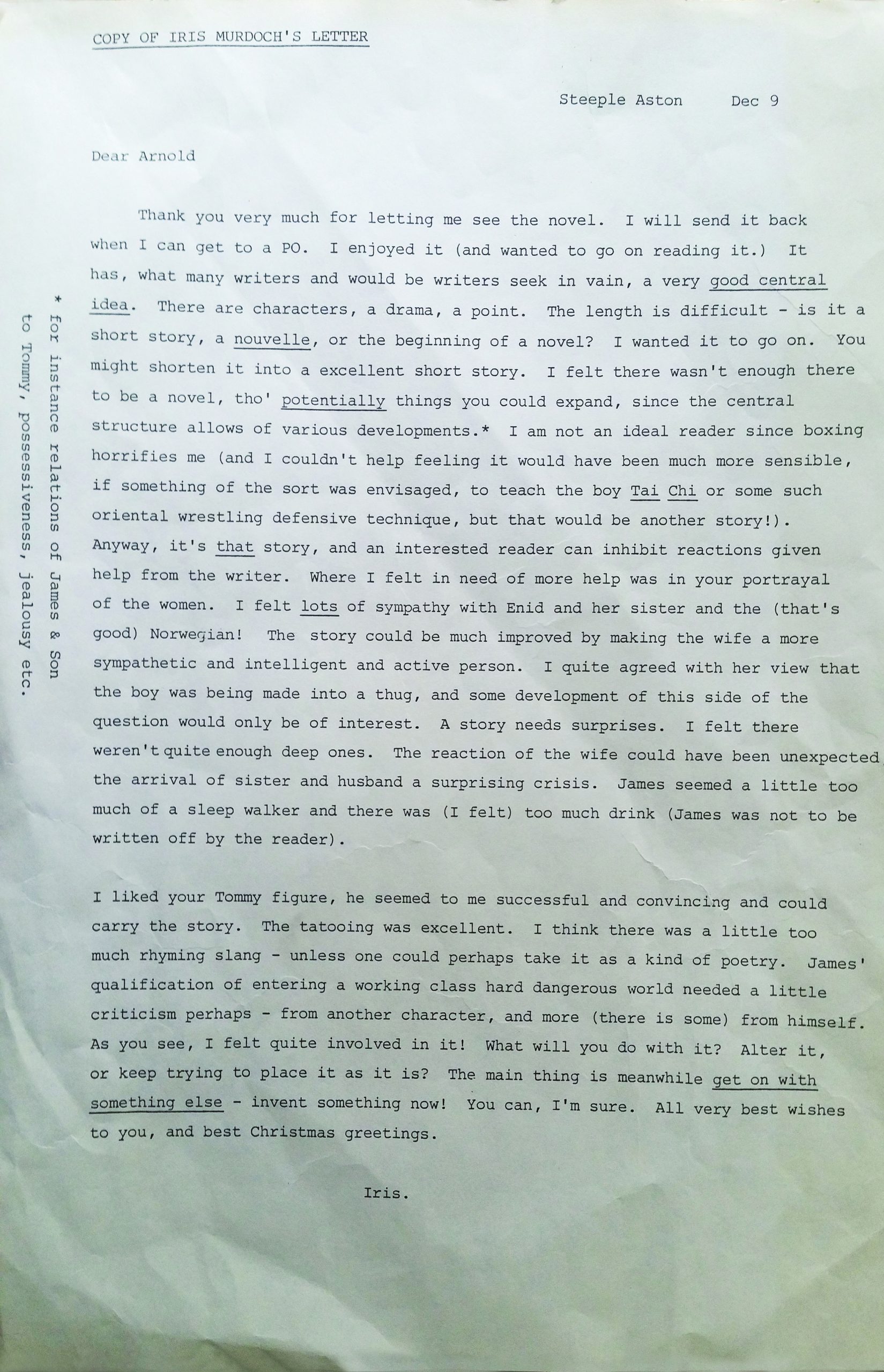

Despite the discrepancies in their drinking habits and the fact that the journal never quite materialised, Arnold and Iris became good friends. I had the sense that, like me, Dr Spector was the sort to take on too many projects with the inevitable consequence of some of them becoming elongated or falling by the wayside. At one stage he was trying to write novels and, at various points, bravely sent them to Murdoch for her opinion. In one instance, she sent him quite a thorough critique which he had typed up and has treasured all these years. The reason I include it here is for the interesting comment: ‘and there was, I felt, too much drink’. Some might say this was pot calling kettle black. On that note, let’s move on to A Fairly Honourable Defeat.

Rupert and Hilda comprise a successful, slightly self-congratulatory couple whose only major worry is their wayward son Peter who has dropped out of Cambridge and gone to live with Tallis, the estranged do-gooding husband of Hilda’s academic philosopher sister Morgan, who, in turn, left Tallis for a now defunct affair with scientist Julius King. Other important characters in the novel are Simon, Rupert’s brother, a sweet-natured, artistic and somewhat flamboyant man who is in a long-term relationship with Axel, a university friend of both Rupert and Julius; and Leonard, comedic foul-mouthed father of Tallis who lives with him in squalor alongside a motley collection of others whose lives are also troubled.

Initially, we observe scenes of apparent domestic bliss that are gradually poisoned by the cavalier Shakespearean manipulations of Julius King. Close to the end of the book, we discover that Julius and Tallis have both suffered unusual evils which offer some explanation of their behaviour; Julius spent the war in Belsen, and Tallis lost his sister to a sexual predator when she was only fourteen, also a terrible tragedy for Leonard, one must assume. Tallis is described as Christ-like as he channels his trauma into trying to improve the world to a seriously self-sacrificing degree, in contrast to both Julius and Leonard whose suffering likely underpins their inclination to visit adversity upon others.

As the story draws to a close, Rupert calamitously drowns in his own swimming pool, particularly so as the truth has been revealed nearly in time to save him. The other characters later rally: Simon and Axel in a strengthened, more honest, relationship; Hilda and Morgan in an apparently man-free Californian paradise; Peter in therapy; Julius swanning around Paris; Tallis being Tallis.

What is the liver? And what is its role in A Fairly Honourable Defeat? The liver is an essential organ found in all vertebrates – it is the largest internal organ (skin is considered the largest organ overall) and it can occupy up to a quarter of body mass in certain species – sharks are the most extreme case in this regard. The liver has important constructive and destructive roles: a bit like Julius King, who contributed first to general scientific understanding, then to weapons development, and now seriously disrupts the lives of most of the characters in A Fairly Honourable Defeat and yet is seen to help selflessly in certain cases, for example, cleaning up the deadly microclimate of Tallis’s kitchen. The liver builds specialised molecules that are essential for our survival while breaking down toxic compounds for removal from the body. It’s a busy multifunctional organ with lots of coordinated activity taking place simultaneously, much like a Murdoch novel. The liver converts our food into useful bodily substances, stores these and dispenses them as needed, neutralises toxins, aids blood clotting, regulates blood sugar, among many other vital functions.

Liver cells generally fall into five varieties, each with a possible paralogue in A Fairly Honourable Defeat:

The most common liver cells are called hepatocytes. They are all-rounders, effecting many of the roles for which the liver is most famous, and are recently shown to spearhead inflammatory response; ‘rallying the troops’ for battle with the long term goal of calming things down. Perhaps this is Tallis, contributing to society through social action and deploying violence when necessary to defuse an injustice. Hilda fits too with some of these functions: volunteering, making places habitable.

Stellate cells are found in dormant and active states, rather like Morgan, with activation triggered by alcohol consumption and liver damage, also rather like Morgan. Stellate cells are responsible for structural reorganisation of collagen, which can contribute to scarring and eventual cirrhosis. I have known a lot of people like Morgan – intelligent, effective characters who lose their minds and sense of responsibility over relationships. We don’t know much about her past drinking habits but, in the novel, she is rarely seen without a drink and her dubious decision-making is nearly always fuelled by alcohol; the significant exception is her unwise clinch with Peter, for which excessive sun and bucolic euphoria get the blame. ‘I’ve been crying whisky for the last six months. I think I must have undergone a chemical change’, declares Morgan (FHD 45). Although intended as metaphor, this is yet another example of Murdoch’s prescience: alcohol consumption can now be determined through the analysis of tears. In 1991, Canadian scientists patented a device that measures tear-alcohol content in 15 seconds and represents a potential alternative to the breathalyser used by traffic police (11). Many related technologies have followed. In 2019, an international team from Spain, Brazil and the United States designed and tested a pair of glasses, incorporating biosensors and a microfluidics system to collect tears from the wearer, that is able to report on levels of alcohol, glucose and other biomarkers, suitable for a wide range of healthcare and forensic applications (12).

Cholangiocytes are the second most abundant cells in the liver and form the lining of the bile ducts, modifying the bile as it passes through. Leonard and Peter also sit around and generate a lot of bile over the course of the novel.

Sinusoidal endothelial cells are specialised gatekeepers that arrange themselves into a barrier that selectively allows traffic of particles within a particular size range between capillaries and the main liver tissue. Axel and Julius could be said to fall into this category since they both display controlling behaviour, albeit with differing motivations. Julius is a self-described puppeteer throughout his involvement in the ménage, and Axel exerts power over Simon, being especially judgemental about his drinking habits: ‘And for God’s sake Simon, don’t drink too much tonight. Remember, when I start fingering the lobe of my ear, it means I think you’ve had enough’ (FHD 62).

Kupffer cells, named after German anatomist Karl Wilhelm Ritter von Kupffer (1829–1902) who discovered them, are the liver’s macrophages: immune cells that can engulf and eliminate invading microbes. Perhaps this is Simon, the lovable character whose ‘enjoyments were similar in kind though not in degree, whether stroking a cat or a Chippendale chair or drinking a dry martini or looking at a picture by Titian or getting into bed with Axel’ (FHD 29). Simon is quite insecure and relies on drink for courage. ‘It was never too early for Simon to start to drink’ but he regularly does the right thing (FHD 25). His bravest moment in the novel, taking on the racists, is achieved without alcohol and in fact usurps his plan to ‘have a decent drink’ (FHD 212) before the others get a chance to impose the accepted accompaniment to Chinese food – lager or, God forbid, tea (13).

I think a lot about the novel’s title and whether there is anything honourable about Julius King’s value system. He is respected among his friends for his intellect and frankness and he abuses this trust to conduct deceit and undermine their smug existence. There is a lot of interesting literature around the ethics of providing liver transplants to patients who struggle with alcoholism, both in terms of blame for the degradation of the original liver and responsibility for the transplanted organ in the context of limited supply and public support for organ donation (14). These arguments evoke Simone Weil’s thinking about the generational transmission of suffering that influences so much of Murdoch’s work. The beauty of physiological processes is that they aren’t motivated by good or evil and they just get on with things as best they can. As Rupert says to Hilda early on in A Fairly Honourable Defeat, ‘You can’t cheat nature, you can’t cheat biology’ (FHD 13). Many of the worst killer diseases evade early detection because of the myriad compensatory mechanisms that exist in our bodies and usually tend to work in our favour. Earlier detection of Julius King’s subterfuge would have saved Rupert’s life, but would Axel, Simon, Hilda and Morgan have experienced the jolts that steered their lives towards more authentic courses? And who would be happier? Who sadder? Some things change some stay the same. Peter is still a leeching pawn in the quest of others for his own improvement. Tallis still does too much and has no time to think. This is all speculation, of course, but it’s also a good way to picture the complex networks of interaction and influence that drive biological processes as well as the plots of good novels.

Notes

1. Iris Murdoch, A Fairly Honourable Defeat (London: Chatto & Windus, 1970), 201, hereafter referenced parenthetically in the text as FHD.

2. Rivka Isaacson, ‘Alzheimer’s Amyloid Analogy: Disease Depicted through A Word Child’ in Iris Murdoch: A Reassessment, ed. by Anne Rowe (Basingstoke; Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 204–213; Rivka Isaacson, ‘Rebarbative Wire?: Compartments and Complexity in The Bell and the Body’ in Iris Murdoch Connected: Critical Essays on Her Fiction and Philosophy, ed. by Mark Luprecht (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 2014), 97–112.

3. Iris Murdoch, 3 October 1979, KUAS80/7/32, Iris Murdoch Collections, Kingston University Archives.

4. Iris Murdoch, The Sea, The Sea (London: Chatto & Windus, 1978), 448.

5. Rachel Hirschler commenting on Facebook survey, 19 April 2024.

6. Michiel Borgman commenting on Facebook survey, 19 April 2024.

7. Charli Connor commenting on Facebook survey, 19 April 2024.

8. Nicola Doig commenting on Facebook survey, 19 April 2024.

9. Tatevik Ayvazan, David Morgan and Daniel Read, commenting on Facebook survey, 19 April 2024.

10. Author’s own transcript.

11. Edmund L. Andrews, ‘Patents; Tears Tested to Measure Alcohol Level’, New York Times, 16 March 1991, https://www.nytimes.com/1991/03/16/business/patents-tears-tested-to-measure-alcohol-level.html [accessed 20 June 2024].

12. Juliane R. Sempionatto et al., ‘Eyeglasses-based tear biosensing system: Non-invasive detection of alcohol, vitamins and glucose’, Biosens Bioelectron, 15 July 2019, vol 137, 161–170, doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2019.04.058. Epub 2019 May 7. PMID: 31096082; PMCID: PMC8372769.

13. Elijah Trefts, Maurine Gannon, David H. Wasserman, The Liver, Curr Biol. 2017 Nov 6;27(21):R1147-R1151, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.019. PMID: 29112863; PMCID: PMC5897118.

14. For example, Diehua Hu and Nadia Primc, ‘Should responsibility be used as a tiebreaker in allocation of deceased donor organs for patients suffering from alcohol-related end-stage liver disease?’, Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 26 June 2023, vol 2, 243-255, doi: 10.1007/s11019-023-10141-3. Epub 2023 Feb 13. PMID: 36780062; PMCID: PMC10175331.