Para-Illustrating Iris Murdoch

‘It is difficult in life to be good, and difficult in art to portray goodness. Perhaps we don't know much about goodness.’

Iris Murdoch

I am an artist and illustrator undertaking a practice-based PhD project at Kingston School of Art titled Para-Illustration: Gaps, fragments and spaces of the literary imagination. My project explores the space between reading and seeing and the literary and visual to propose the practice of para-illustration - a creative process that uses a writer’s notes, drafts and archives as sources for literary images.

The fragmented (para-) material of a writer’s jottings, deletions and traces exist beyond their known and published counterparts. So what happens if we use partial and fragmented versions as sources? What if we look at word changes and deletions, notes on the back of a shopping list, or the circle left by the writer’s coffee cup? How might we read these material ‘incidentals’ as part of the image-making process? And how might the act of illustration be rethought by using these hidden or ignored aspects of ‘writing in progress’ that are usually buried in an archive?

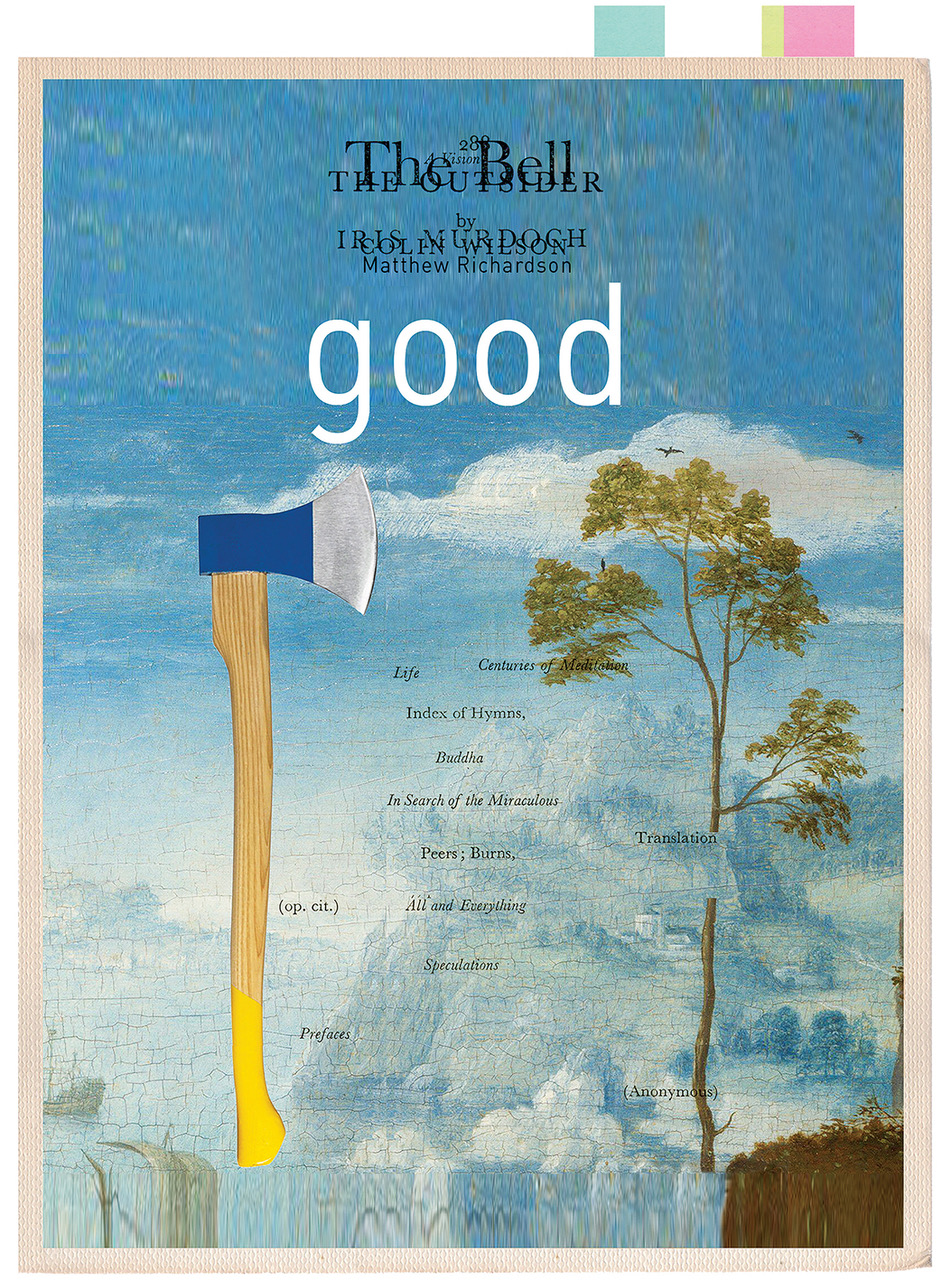

Previously, I have worked with manuscripts and notes of J.G. Ballard and Angela Carter held at the British Library, but during the last two years I have been working on a project that grew out of the Iris Murdoch Collections at Kingston University. The project began with the discovery of some fragmentary notes written by Iris Murdoch in the back pages of The Outsider (1956) by Colin Wilson (1931 - 2013) which Dayna Miller, the Archivist at Kingston University, had drawn my attention to. Murdoch’s notes are her first thoughts for a new novel that later became The Bell (1958). This unique discovery provided the creative spark for exploring the collision between two writers and two literary worlds, culminating in a new bookwork titled Good, which is a kind of book within a book of found and incomplete text fragments and collaged images.

The Bell (1958) explores ideas of separation, morality and the conflict between sex and religion and takes place at Imber Court, a lay retreat and convent of Benedictine nuns. Its main theme is the way individuals function and behave in a materialistic world, and the disharmony between the mind and physical experience of the world. The narrative follows Dora Greenfield, a recently and unhappily married woman, who travels from her home in London to stay at Imber to reconnect with herself and restore a sense of hope.

The Outsider by Colin Wilson looks at the psyche of the artist as outsider through the lives and works of writers and artists, including Albert Camus, Van Gogh and William Blake. The Outsider is the book by which he is most remembered and associated. During the decades after its publication, his writings, reflecting increasingly eccentric ideas on mysticism, the occult and the paranormal, were not well reviewed or received.

It is not known if the two writers met. The inscription in the front of the book he sent reads: ‘For Iris, with admiration for her work & warmest affection - & confidence that she will be among the writers who will create a new Elizabethan age. Love from Colin.’ Sadly, Iris didn’t exactly return Colin’s admiration, and is dismissive of 'asses like Colin Wilson' in a private letter to her friend, Brigid Brophy!

Murdoch’s notes don’t occur in the margins of Wilson’s words as critique, or as notes to self, but as a separate entity in the back pages of his book. How do we understand this writing? Were they notes inspired by what she had read in Wilson’s text, or were the endpapers just a convenient notebook that happened to be close at hand when inspiration struck? We can’t know, but these thoughts inspired my use of both chance and structure as organising principles in my intermingled visual narrative.

My aim in making Good was to translate the experience of reading and seeing, and the physical sense of handling and discovery that the literary archive offers. Bibliography is the science and study of books. ‘Bibli’ means book and has its entymological roots all the way back in the Bible - the ‘good book’. In Murdoch’s philosophy, ‘good’ substitutes for ‘god’. I wanted to use the form and the object of the book to play with this idea and as a way to think about ideas of origin and authority. The physical book is an intimate object. We don’t view it like a film, or a picture on the wall, we hold it, weigh it in our hands, take it to bed, spill coffee on it, travel with it. It is a discrete and shareable object.

In looking for a way to develop images for the book, I was drawn to a scene in The Bell, where a stressed Dora visits the National Gallery:

‘Dora had been in the National Gallery a thousand times and the pictures were almost as familiar to her as her own face. Passing between them now, as through a well-loved grove, she felt a calm descending her … Her footsteps took her to various shrines to which she had worshipped so often before: the great light spaces of Italian pictures, more vast and southern than any real South, the angels of Botticelli, radiant as birds, delighted as gods, and circling like the tendrils of a vine … Her heart was filled with love for the pictures, their authority, their marvellous generosity, their splendour. It occurred to her that here at last was something real and something perfect … She felt she had had a revelation.’ (pp.190-191)

Visiting in 1958, Dora is absorbed in the materiality and aura of the paintings. In 2022, my ‘reality’ was through the National Gallery’s image library. The high-resolution scans allowed me to zoom in onto incredible detail. Had I got as close to the paintings as Dora, or had these paintings, digitally reproduced and turned into mere ‘images’, lost their power? I looked at the cracked surfaces, at fragments of gesture, colour, objects and nature. By re-using the sensual and tactile cracked surfaces and details of painted cloth, grass and skin, I wanted to represent the conflict of Dora’s dilemma, between carnal and religious love - between flesh and ‘the word’. In some of the images, geometric, repeating and symmetrical configurations of fragmented details and symbols act as mandalas - images of transcendence that also find an echo in the visual structuring of spiritualist Outsider Art.

Both The Bell and The Outsider deal with ideas of a ‘beyond’ and an ‘outside’ experience. In The Bell, boundaries and thresholds – walls, gates, doors and bars – are metaphors of social, religious and moral structures, and in my book, these aspects find an echo in pages, frames, markers and divisions. Murdoch makes use of doubles and pairs – two bells, twins, two communities – as a way to describe alternative possibilities, actions and spaces. I used this ‘doubling’ in contrastive landscapes, almost like a ‘spot the difference’, to create movement and a visually rhythmic pattern that correlates with a structured monastic day, marked out by the sound of a bell. The surface and depth and of the lake – an important symbolic space in The Bell – was used as a structural form to visually ascend and descend through the book. Words and images fall through and across layers and levels, on pages, and post-it notes, on turned corners and in margins. I wanted to encourage the reader to explore literary space as something that is forever ‘in-process’ and transcends boundaries and thresholds, even as it remains a physical thing held in the hand. As Murdoch said, ‘every book is the wreck of a perfect idea’.

Making Good is showing from 5 June – 7 September at Kingston University Archive, Floor 2, Town House, Penrhyn Road, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey KT1 2EE. Contact archives@kingston.ac.uk for more information. The exhibition is a curated collaboration between Matthew Richardson, Dayna Miller, Kingston University Archivist and Frances White, Deputy Director of the Iris Murdoch Research Centre, University of Chichester.

More images and information at: https://matthew-richardson.co.uk/Good